CNC Machining Technology of Piston Special-Shaped Pin Holes

Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machining technology has revolutionized the manufacturing of precision components in modern engineering, particularly in the production of internal combustion engine parts such as pistons. Among the most intricate and critical features of a piston are its pin holes, which serve as the connection point between the piston and the connecting rod via the piston pin (also known as a gudgeon pin or wrist pin). While traditional cylindrical pin holes have long been standard, the advent of special-shaped pin holes—non-circular, asymmetrical, or contoured designs—has introduced new challenges and opportunities in piston design and performance optimization. This article explores the CNC machining technology employed in crafting special-shaped pin holes in pistons, delving into the historical evolution, scientific principles, machining processes, tool design, material considerations, and comparative analyses of techniques, supported by detailed tables.

Historical Context and Evolution

The development of piston pin holes reflects the broader evolution of internal combustion engine technology. Early pistons, dating back to the 19th century with the invention of the Otto cycle engine by Nikolaus Otto in 1876, featured simple cylindrical pin holes machined using manual lathes or basic drilling equipment. These designs prioritized ease of manufacturing over performance optimization, as the tools and techniques of the era lacked the precision required for complex geometries. The pin hole’s primary function—allowing the piston to pivot relative to the connecting rod—remained unchanged, but as engine power and efficiency demands grew in the 20th century, so did the need for enhanced durability and reduced weight.

The introduction of CNC machining in the mid-20th century, pioneered by John T. Parsons and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the 1940s and 1950s, marked a turning point. Initially developed for aerospace applications, CNC technology enabled the precise control of cutting tools via computer programming, allowing manufacturers to produce intricate shapes with tolerances in the micrometer range. By the 1980s, automotive and aerospace industries began adopting CNC machining for piston production, including the exploration of non-circular pin holes to address specific mechanical challenges, such as thermal expansion, stress distribution, and oil flow.

Special-shaped pin holes emerged as a response to these challenges. For instance, oval or bell-shaped pin holes, which deviate from the traditional circular profile, were designed to mitigate fatigue cracking under high-pressure conditions in high-performance engines, such as those used in Formula 1 racing or marine diesel applications. The integration of CNC machining with advanced computer-aided design (CAD) and computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) software further enabled the precise replication of these complex geometries, setting the stage for modern piston manufacturing.

Scientific Principles Underpinning Special-Shaped Pin Holes

The design and machining of special-shaped pin holes are grounded in several scientific disciplines, including mechanics, materials science, and thermodynamics. At the core of this technology is the need to balance structural integrity, thermal performance, and frictional efficiency within the piston assembly.

- Mechanics and Stress Distribution: In a traditional cylindrical pin hole, the contact pressure between the piston pin and the hole’s inner surface is distributed relatively uniformly under ideal conditions. However, under high loads—such as those experienced in turbocharged or high-compression engines—this uniformity can break down, leading to localized stress concentrations and eventual fatigue failure. Special-shaped pin holes, such as flared or oval profiles, redistribute these stresses more evenly across the contact surface. Finite element analysis (FEA) studies have shown that a bell-shaped pin hole, for example, can reduce peak contact pressure by up to 30% compared to a cylindrical hole, as demonstrated in research by Luigi Bianco in 2010.

- Thermal Dynamics: Pistons operate in extreme thermal environments, with temperatures in the combustion chamber reaching upwards of 600°C (1112°F). The pin hole region, though farther from the combustion zone, still experiences significant heat transfer from the piston crown. Special-shaped pin holes can enhance oil flow and heat dissipation by incorporating contours that align with lubricant pathways, reducing the risk of thermal distortion or seizure. This is particularly critical in aluminum pistons, which have a high thermal expansion coefficient (approximately 23 × 10⁻⁶ K⁻¹).

- Tribology: The interaction between the piston pin and the pin hole involves complex tribological phenomena, including friction, wear, and lubrication. A non-circular pin hole can be engineered to optimize the oil film thickness between the pin and the hole, reducing wear under oscillatory motion. For instance, an oval pin hole may provide a larger contact area during the power stroke, enhancing stability and reducing scuffing.

These principles inform the CNC machining process, requiring precise control over tool paths, cutting parameters, and surface finishes to achieve the desired geometry and performance characteristics.

CNC Machining Processes for Special-Shaped Pin Holes

CNC machining of special-shaped pin holes involves a multi-step process that integrates advanced equipment, tooling, and programming. Below is a detailed examination of the key stages, with an emphasis on scientific rigor and practical application.

1. Design and Programming

The process begins with the creation of a digital model using CAD software, such as SolidWorks, CATIA, or Siemens NX. The special-shaped pin hole geometry—whether oval, bell-shaped, or multi-segmented—is defined based on engineering requirements, often validated through FEA simulations to predict stress and thermal behavior. For example, a typical bell-shaped pin hole might feature a circular entry transitioning to an elliptical or flared profile deeper within the piston skirt, with dimensions such as a 20 mm diameter at the entry and a 22 mm major axis at the deepest point.

Once the design is finalized, CAM software (e.g., Mastercam or Fusion 360) generates a toolpath by translating the 3D model into G-code, the programming language that instructs the CNC machine. The toolpath must account for the non-linear contours of the pin hole, often requiring 3-axis or 5-axis machining to achieve the necessary precision. Interpolation techniques, such as helical milling, are commonly employed to ensure smooth transitions between curved surfaces.

2. Material Selection and Preparation

Pistons are typically made from aluminum alloys (e.g., 4032 or 2618) or steel (e.g., 42CrMoA), chosen for their strength, thermal conductivity, and machinability. Aluminum alloys dominate automotive applications due to their lightweight properties (density ≈ 2.7 g/cm³), while steel is preferred in heavy-duty diesel engines for its higher tensile strength (up to 1000 MPa). The raw material is cast or forged into a near-net-shape piston blank, minimizing material removal during machining.

Prior to CNC machining, the blank is heat-treated to enhance its mechanical properties. For aluminum, a T6 temper (solution heat treatment followed by artificial aging) increases hardness to approximately 130 HB (Brinell hardness), improving resistance to wear in the pin hole region. The blank is then clamped onto the CNC machine’s fixture, ensuring alignment to within 0.01 mm to prevent dimensional errors.

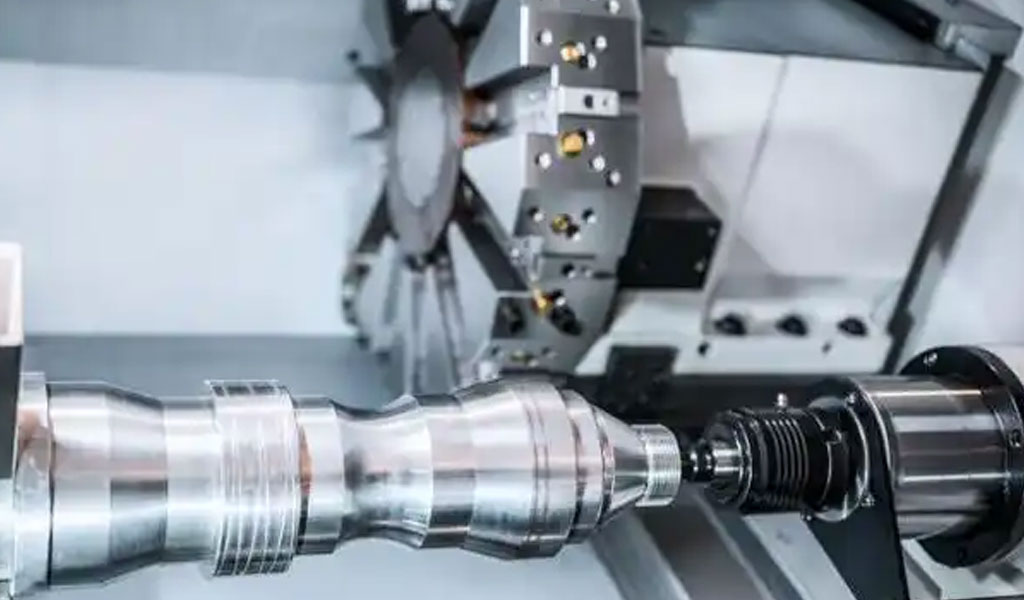

3. Rough Machining

Rough machining removes excess material from the piston blank to approximate the pin hole’s shape. This step typically employs a CNC lathe or milling machine equipped with a carbide end mill or boring tool. For a special-shaped pin hole, roughing may involve multiple passes with progressively smaller tools to define the basic contour. Cutting parameters—such as spindle speed (e.g., 2000–3000 RPM), feed rate (0.1–0.3 mm/rev), and depth of cut (1–3 mm)—are optimized to balance material removal rate with tool life.

Coolant, often a water-based emulsion, is applied to manage heat generation, which can exceed 200°C at the tool-workpiece interface. Excessive heat risks work hardening in aluminum or thermal cracking in steel, both of which compromise subsequent finishing operations.

4. Finish Machining

Finish machining refines the pin hole to its final geometry and surface quality, critical for ensuring proper fit with the piston pin and minimizing wear. This step often requires specialized CNC equipment, such as the Takisawa TPS-3300HII, designed specifically for non-circular piston pin hole machining. The TPS series employs a combination of lathe and machining center capabilities, using a spiral scraping method to achieve mirror-like finishes (Ra < 0.2 μm).

For a bell-shaped pin hole, finish machining might involve:

- Initial Boring: A precision boring bar with a diamond-tipped insert establishes the entry diameter and depth.

- Contouring: A ball-end mill or custom-profiled tool traces the flared or oval profile, guided by 5-axis motion to maintain accuracy along the curved surfaces.

- Burnishing: A secondary operation using a roller or ball burnishing tool smooths the surface, enhancing fatigue resistance by inducing compressive residual stresses.

Tolerances are typically held to ±0.005 mm, with surface roughness values below Ra 0.4 μm, as specified in ISO 1302 standards. In-process measurement systems, such as laser probes or touch probes, verify dimensions in real time, reducing the risk of scrap.

5. Post-Processing and Inspection

After machining, the pin hole undergoes deburring to remove microscopic burrs that could abrade the piston pin. Chemical cleaning or ultrasonic washing removes coolant residue and machining debris. Final inspection employs coordinate measuring machines (CMM) or optical profilometers to confirm geometric accuracy and surface integrity. For high-performance pistons, additional tests—such as dye penetrant inspection for micro-cracks or hardness testing (e.g., Rockwell or Vickers)—ensure compliance with design specifications.

Tooling and Equipment

The complexity of special-shaped pin holes necessitates advanced tooling and CNC machines tailored to the task. Key examples include:

- Cutting Tools: Carbide or polycrystalline diamond (PCD) tools are preferred for their hardness (up to 2000 HV) and wear resistance. Custom-profiled tools, such as those with flared or elliptical cutting edges, are often designed in-house to match the pin hole geometry.

- CNC Machines: 5-axis CNC machining centers, such as the DMG Mori DMU series, offer the flexibility to navigate complex contours. Dedicated piston machining systems, like the Nidec TPS series, integrate high-speed spindles (up to 10,000 RPM) and ceramic mechanisms for ultra-precision.

- Fixtures: Vacuum chucks or hydraulic clamps secure the piston blank, minimizing vibration and distortion during high-speed cutting.

Tool wear is a significant concern, as the interrupted cuts required for non-circular shapes accelerate flank wear and cratering. Tool life can be extended through coatings (e.g., TiAlN or DLC) and optimized cutting parameters, informed by empirical models like the Taylor tool life equation:

VTn=CV T^n = C where V V is cutting speed, T T is tool life, n n is a material-dependent exponent, and C C is a constant.

Comparative Analysis of Techniques

To illustrate the diversity of CNC machining approaches for special-shaped pin holes, the following table compares three prominent techniques: traditional drilling/boring, helical interpolation milling, and electrochemical machining (ECM) as an alternative non-traditional method.

| Parameter | Traditional Drilling/Boring | Helical Interpolation Milling | Electrochemical Machining (ECM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geometry Capability | Limited to cylindrical or tapered | Oval, bell-shaped, multi-contour | Complex 3D shapes |

| Tooling | Standard drills, boring bars | Ball-end mills, custom tools | Cathode electrodes |

| Material Removal Rate | High (10–20 cm³/min) | Moderate (5–15 cm³/min) | Low (1–5 cm³/min) |

| Surface Finish (Ra) | 0.8–1.6 μm | 0.2–0.4 μm | 0.1–0.3 μm |

| Tolerance | ±0.01 mm | ±0.005 mm | ±0.002 mm |

| Heat Affected Zone (HAZ) | Moderate (50–100 μm) | Low (20–50 μm) | None |

| Tool Wear | High | Moderate | None (non-contact) |

| Cycle Time | 5–10 min | 8–15 min | 15–30 min |

| Cost per Part | Low ($5–10) | Moderate ($10–20) | High ($20–50) |

| Applications | General automotive pistons | High-performance engines | Aerospace, precision dies |

Analysis:

- Traditional Drilling/Boring: Best suited for simple pin holes due to its speed and cost-effectiveness but lacks the flexibility for special shapes.

- Helical Interpolation Milling: Offers a balance of precision and versatility, making it the dominant CNC method for special-shaped pin holes in automotive and racing applications.

- ECM: Excels in surface finish and tolerance but is slower and more expensive, limiting its use to niche, high-value components.

Material-Specific Considerations

The choice of piston material influences machining strategy. The table below compares aluminum alloy (4032) and steel (42CrMoA) in the context of special-shaped pin hole machining.

| Property | Aluminum 4032 | Steel 42CrMoA |

|---|---|---|

| Density | 2.68 g/cm³ | 7.85 g/cm³ |

| Tensile Strength | 380 MPa | 1080 MPa |

| Thermal Conductivity | 155 W/m·K | 42 W/m·K |

| Machinability Rating | High (90%) | Moderate (50%) |

| Cutting Speed | 200–300 m/min | 50–100 m/min |

| Tool Wear Rate | Low | High |

| Typical Application | Automotive pistons | Marine diesel pistons |

Insights:

- Aluminum’s high machinability allows faster cutting speeds and reduced tool wear, ideal for high-volume production.

- Steel’s greater strength requires slower speeds and robust tooling, suited to heavy-duty applications where durability trumps cost.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite its advancements, CNC machining of special-shaped pin holes faces several challenges:

- Tool Path Optimization: Complex geometries increase programming time and computational load, necessitating more efficient CAM algorithms.

- Thermal Management: Heat buildup in deep pin holes can distort dimensions, requiring advanced coolant delivery systems.

- Cost: The need for custom tools and 5-axis machines raises production costs, limiting adoption in budget-conscious sectors.

Future developments may include:

- Additive Manufacturing Integration: Hybrid processes combining CNC machining with 3D printing could pre-form pin hole contours, reducing machining time.

- AI-Driven Machining: Machine learning algorithms could optimize tool paths and cutting parameters in real time, enhancing efficiency.

- Sustainable Practices: Advances in dry machining or minimum quantity lubrication (MQL) could reduce environmental impact, aligning with global sustainability goals.

Conclusion

CNC machining technology for piston special-shaped pin holes represents a pinnacle of precision engineering, blending mechanical innovation with scientific rigor. From its origins in basic drilling to its current role in crafting intricate, performance-enhancing geometries, this technology has transformed piston design and manufacturing. Through detailed processes, specialized equipment, and rigorous analysis, CNC machining ensures that special-shaped pin holes meet the exacting demands of modern engines. As research and technology evolve, the field promises further breakthroughs, solidifying its place at the forefront of engineering excellence.

Reprint Statement: If there are no special instructions, all articles on this site are original. Please indicate the source for reprinting:https://www.cncmachiningptj.com/,thanks!

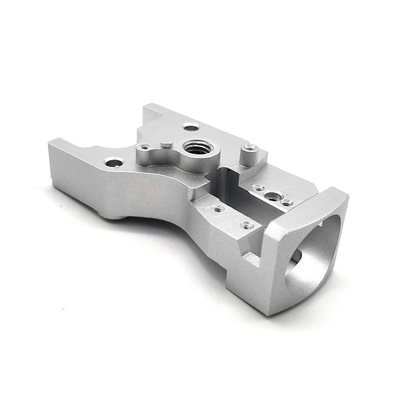

3, 4 and 5-axis precision CNC machining services for aluminum machining, beryllium, carbon steel, magnesium, titanium machining, Inconel, platinum, superalloy, acetal, polycarbonate, fiberglass, graphite and wood. Capable of machining parts up to 98 in. turning dia. and +/-0.001 in. straightness tolerance. Processes include milling, turning, drilling, boring, threading, tapping, forming, knurling, counterboring, countersinking, reaming and laser cutting. Secondary services such as assembly, centerless grinding, heat treating, plating and welding. Prototype and low to high volume production offered with maximum 50,000 units. Suitable for fluid power, pneumatics, hydraulics and valve applications. Serves the aerospace, aircraft, military, medical and defense industries.PTJ will strategize with you to provide the most cost-effective services to help you reach your target,Welcome to Contact us ( sales@pintejin.com ) directly for your new project.

3, 4 and 5-axis precision CNC machining services for aluminum machining, beryllium, carbon steel, magnesium, titanium machining, Inconel, platinum, superalloy, acetal, polycarbonate, fiberglass, graphite and wood. Capable of machining parts up to 98 in. turning dia. and +/-0.001 in. straightness tolerance. Processes include milling, turning, drilling, boring, threading, tapping, forming, knurling, counterboring, countersinking, reaming and laser cutting. Secondary services such as assembly, centerless grinding, heat treating, plating and welding. Prototype and low to high volume production offered with maximum 50,000 units. Suitable for fluid power, pneumatics, hydraulics and valve applications. Serves the aerospace, aircraft, military, medical and defense industries.PTJ will strategize with you to provide the most cost-effective services to help you reach your target,Welcome to Contact us ( sales@pintejin.com ) directly for your new project.

- 5 Axis Machining

- Cnc Milling

- Cnc Turning

- Machining Industries

- Machining Process

- Surface Treatment

- Metal Machining

- Plastic Machining

- Powder Metallurgy Mold

- Die Casting

- Parts Gallery

- Auto Metal Parts

- Machinery Parts

- LED Heatsink

- Building Parts

- Mobile Parts

- Medical Parts

- Electronic Parts

- Tailored Machining

- Bicycle Parts

- Aluminum Machining

- Titanium Machining

- Stainless Steel Machining

- Copper Machining

- Brass Machining

- Super Alloy Machining

- Peek Machining

- UHMW Machining

- Unilate Machining

- PA6 Machining

- PPS Machining

- Teflon Machining

- Inconel Machining

- Tool Steel Machining

- More Material