Balance Optimization of Flexible Machining Production Lines for Complex Box Parts

Flexible machining production lines represent a cornerstone of modern manufacturing, particularly in industries requiring high adaptability and precision, such as aerospace, automotive, and heavy machinery. These systems are designed to handle a variety of complex parts with minimal reconfiguration, offering a balance between the efficiency of dedicated production lines and the versatility of job shops. Among the diverse applications of flexible machining systems, the production of complex box parts—structural components characterized by intricate geometries, multiple machined features, and tight tolerances—presents unique challenges and opportunities for optimization. Balance optimization, in this context, refers to the process of distributing workloads, minimizing bottlenecks, and maximizing throughput while maintaining flexibility and cost-effectiveness. This article explores the principles, methodologies, challenges, and technological advancements associated with optimizing the balance of flexible machining production lines for complex box parts, drawing from scientific literature and practical implementations.

Overview of Flexible Machining Production Lines

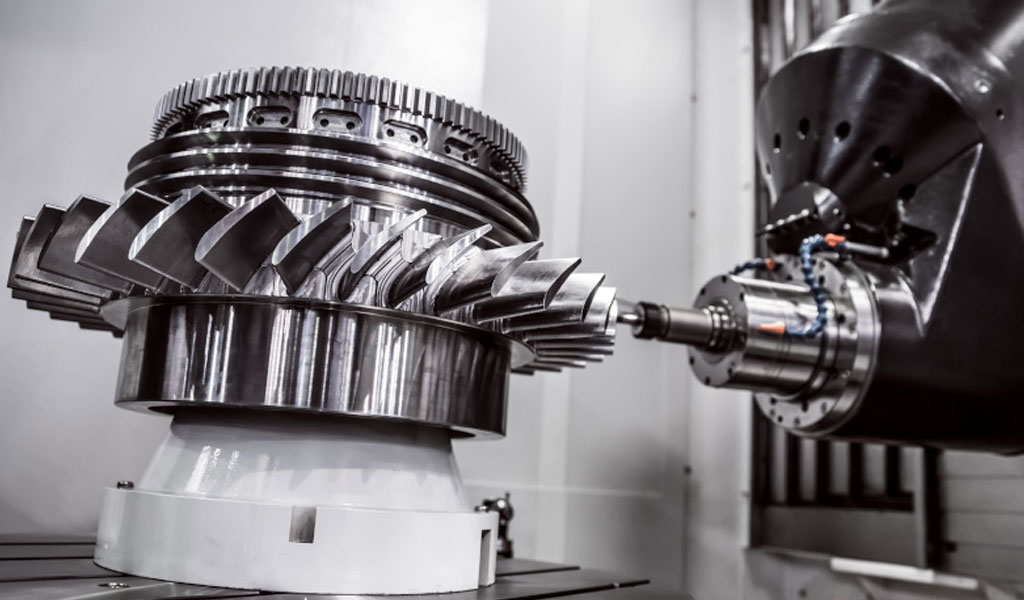

A flexible machining production line (FMPL) is an integrated system comprising computer numerical control (CNC) machines, automated material handling systems, and centralized control software, capable of adapting to changes in product type, volume, and design with minimal downtime. Unlike rigid production lines optimized for high-volume, single-part production, FMPLs excel in mid-volume, high-variety scenarios, making them ideal for complex box parts such as gearbox housings, engine blocks, or structural frames. These parts often feature multiple surfaces requiring milling, drilling, boring, and tapping, with interrelated tolerances that demand precise sequencing and coordination.

The concept of balance in an FMPL involves ensuring that each workstation or machine operates at an optimal load, avoiding idle time (underutilization) or excessive queuing (overburdening). For complex box parts, this balance is complicated by the diversity of machining tasks, tool changes, setup requirements, and interdependencies between operations. Optimization thus requires a multidisciplinary approach, integrating mechanical engineering, operations research, and advanced computational techniques.

Characteristics of Complex Box Parts

Complex box parts are typically prismatic components with a rectangular or cubic base geometry, often hollow or semi-hollow, and featuring multiple machined elements such as holes, slots, pockets, and threads. These parts are prevalent in industries where structural integrity and precision are paramount. For example, an aerospace gearbox housing might include dozens of mounting holes, internal cavities for gear placement, and external surfaces for mating with other components, each with tolerances in the range of ±0.01 mm. The complexity arises from:

- Geometric Variability: Multiple faces and features requiring machining from different angles, often necessitating multi-axis CNC machines.

- Task Precedence: Operations must follow a specific sequence (e.g., rough milling before finish boring) to maintain dimensional accuracy.

- Material Properties: Box parts are often made from high-strength alloys like aluminum, titanium, or steel, which affect machining parameters and tool wear.

- Volume and Variety: Production demands may range from small batches (e.g., 50 units) to medium runs (e.g., 15,000 units annually), with frequent design variations.

These characteristics make balance optimization a critical factor in ensuring efficient production while meeting quality and cost objectives.

Principles of Balance Optimization

Balance optimization in FMPLs aims to achieve several key objectives: minimizing cycle time, reducing idle time, eliminating bottlenecks, and maximizing resource utilization. For complex box parts, this involves addressing both the spatial and temporal aspects of production. The primary principles include:

- Workload Distribution: Assigning machining tasks to workstations such that each machine’s processing time approximates the line’s takt time (the rate at which parts must be completed to meet demand).

- Task Sequencing: Determining the optimal order of operations to satisfy precedence constraints and minimize setup changes.

- Resource Allocation: Matching tools, fixtures, and machines to tasks based on capability and availability.

- Flexibility Maintenance: Ensuring the line can adapt to design changes or production volume fluctuations without significant reconfiguration.

Mathematically, the balancing problem can be framed as a combinatorial optimization challenge, often classified as NP-hard due to its computational complexity. For a production line with n n tasks and m m workstations, the goal is to assign tasks to workstations such that the maximum workstation time (cycle time) is minimized, subject to precedence constraints and capacity limits.

Methodologies for Balance Optimization

Several methodologies have been developed to address balance optimization in FMPLs, ranging from traditional mathematical programming to modern heuristic and simulation-based approaches. These methods are particularly tailored to the challenges posed by complex box parts.

Mathematical Programming

Mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) is a common approach for formulating the line balancing problem. Consider a simplified model where T={t1,t2,...,tn} T = \{t_1, t_2, ..., t_n\} represents the set of machining tasks, W={w1,w2,...,wm} W = \{w_1, w_2, ..., w_m\} the set of workstations, and pi p_i the processing time of task ti t_i . The objective is to minimize the cycle time C C , defined as:

C=maxj∈W∑i∈Tjpi C = \max_{j \in W} \sum_{i \in T_j} p_i

where Tj T_j is the subset of tasks assigned to workstation wj w_j . Constraints include:

- Assignment Constraint: Each task is assigned to exactly one workstation. ∑j∈Wxij=1,∀i∈T \sum_{j \in W} x_{ij} = 1, \quad \forall i \in T where xij=1 x_{ij} = 1 if task ti t_i is assigned to workstation wj w_j , and 0 otherwise.

- Precedence Constraint: If task ti t_i must precede task tk t_k , then ti t_i must be assigned to a workstation no later than tk t_k . ∑j=1mj⋅xij≤∑j=1mj⋅xkj,∀(i,k)∈P \sum_{j=1}^m j \cdot x_{ij} \leq \sum_{j=1}^m j \cdot x_{kj}, \quad \forall (i, k) \in P where P P is the set of precedence pairs.

- Capacity Constraint: The total processing time at each workstation must not exceed C C . ∑i∈Tpi⋅xij≤C,∀j∈W \sum_{i \in T} p_i \cdot x_{ij} \leq C, \quad \forall j \in W

For complex box parts with dozens of tasks (e.g., 73 tasks as in a typical case study), solving this model exactly becomes computationally infeasible, prompting the use of heuristic or metaheuristic methods.

Heuristic and Metaheuristic Approaches

Heuristic methods, such as the Ranked Positional Weight (RPW) technique, prioritize tasks based on their processing times and precedence relationships, assigning them to workstations sequentially. However, these methods may not guarantee optimality, especially for complex systems. Metaheuristic algorithms, including Genetic Algorithms (GA), Simulated Annealing (SA), and Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), offer more robust solutions by exploring a larger solution space.

For instance, an enhanced hybrid ACO approach, as applied to complex box parts, incorporates task set filtering to handle compound constraints (e.g., tool changes, station preparation). The algorithm models the production line as a graph, with ants constructing feasible task assignments by depositing pheromones based on solution quality. The dual objectives—minimizing the number of workstations and maximizing the balancing rate—are balanced using a weighted fitness function:

F=w1⋅(1/m)+w2⋅BR F = w_1 \cdot (1 / m) + w_2 \cdot BR where BR=(∑j∈WTj)/(m⋅C) BR = ( \sum_{j \in W} T_j ) / ( m \cdot C ) is the balancing rate, and w1,w2 w_1, w_2 are weights reflecting priority.

Simulation-Based Optimization

Simulation tools like Visual Slam or Arena allow engineers to model the FMPL dynamically, accounting for stochastic factors such as machine breakdowns, tool wear, and material flow variability. For a complex box part with 73 tasks, a simulation might reveal that a bottleneck at a drilling station delays downstream milling operations. By iteratively adjusting task assignments and running simulations, an optimal balance can be approximated. Petri nets, a graphical modeling tool, are often integrated with simulation to analyze deadlock scenarios and ensure smooth material flow.

Technological Enablers

Advancements in Industry 4.0 technologies have significantly enhanced balance optimization for FMPLs producing complex box parts. Key enablers include:

- Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS): Real-time monitoring of machine states and task progress enables dynamic rebalancing in response to disruptions.

- Internet of Things (IoT): Sensors on CNC machines and material handling systems provide data for predictive maintenance and load balancing.

- Artificial Intelligence (AI): Machine learning algorithms can predict optimal task assignments based on historical production data, improving over time.

- Digital Twins: A virtual replica of the FMPL allows engineers to test balancing strategies without interrupting physical production.

For example, a digital twin of a line producing gearbox housings could simulate the impact of adding a second drilling machine, revealing a 15% reduction in cycle time.

Case Study: Balancing a Production Line for a Complex Box Part

Consider a hypothetical complex box part, a gearbox housing with 73 machining tasks, produced at an annual volume of 13,000–15,000 units (260–300 units weekly, 22–25 units per 8-hour shift). The tasks include milling surfaces, drilling mounting holes, boring gear bores, and deburring, with processing times ranging from 2 to 25 minutes. The FMPL comprises five workstations, each equipped with a multi-axis CNC machine and shared material handling system.

Using an MILP model, the initial assignment yields a cycle time of 30 minutes, with significant idle time at two stations due to uneven task distribution. Applying an ACO algorithm with simulation reduces the cycle time to 24 minutes, achieving a balancing rate of 92%. Table 1 compares the two approaches:

Table 1: Comparison of Balancing Methods for Gearbox Housing Production Line

| Method | Number of Workstations | Cycle Time (min) | Balancing Rate (%) | Idle Time (min/shift) | Throughput (units/shift) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MILP (Initial) | 5 | 30 | 78 | 40 | 16 |

| ACO + Simulation | 5 | 24 | 92 | 12 | 25 |

The ACO approach minimizes bottlenecks by redistributing drilling tasks across two stations and optimizing tool change sequences, aligning throughput with the target of 22–25 units per shift.

Challenges in Balance Optimization

Despite these advancements, several challenges persist:

- Complexity Scaling: As the number of tasks and workstations increases, the computational effort for optimization grows exponentially.

- Dynamic Variability: Fluctuations in demand, machine availability, or material properties require real-time adjustments that static models cannot address.

- Cost Constraints: Adding machines or advanced technologies to improve balance increases capital expenditure, necessitating a cost-benefit analysis.

- Human Factors: Skilled operators are needed to oversee and adjust the FMPL, introducing variability in performance.

For complex box parts, the interplay of tight tolerances and task interdependencies further complicates balancing efforts, often requiring hybrid approaches that combine multiple methodologies.

Comparative Analysis of Optimization Techniques

Table 2 provides a detailed comparison of optimization techniques applied to FMPLs for complex box parts, based on criteria such as computational efficiency, solution quality, and adaptability.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Optimization Techniques

| Technique | Computational Time | Solution Quality | Adaptability to Variability | Applicability to Complex Parts | Example Tool/Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MILP | High (hours) | Optimal | Low | Moderate | CPLEX |

| RPW Heuristic | Low (minutes) | Suboptimal | Moderate | High | Manual/Excel |

| Genetic Algorithm | Moderate (hours) | Near-Optimal | High | High | MATLAB |

| ACO | Moderate (hours) | Near-Optimal | High | Very High | Python/Custom |

| Simulation | High (days) | Near-Optimal | Very High | Very High | Arena/Visual Slam |

Simulation excels in handling variability but requires significant setup time, while ACO offers a balance of quality and adaptability, making it well-suited for complex box parts.

Future Directions

The future of balance optimization in FMPLs lies in deeper integration of AI and real-time data analytics. Reinforcement learning could enable systems to autonomously adjust task assignments based on live feedback, while additive manufacturing (e.g., hybrid processes combining 3D printing and machining) could reduce the number of tasks by pre-forming features. Additionally, sustainability considerations—minimizing energy use and material waste—will increasingly influence optimization objectives.

Conclusion

Balance optimization of flexible machining production lines for complex box parts is a multifaceted challenge requiring a blend of theoretical models, computational tools, and practical engineering insights. By leveraging advanced methodologies and technologies, manufacturers can achieve efficient, adaptable production systems that meet the demands of modern industry. The ongoing evolution of these approaches promises even greater precision and flexibility, solidifying the role of FMPLs in the future of manufacturing.

Reprint Statement: If there are no special instructions, all articles on this site are original. Please indicate the source for reprinting:https://www.cncmachiningptj.com/,thanks!

3, 4 and 5-axis precision CNC machining services for aluminum machining, beryllium, carbon steel, magnesium, titanium machining, Inconel, platinum, superalloy, acetal, polycarbonate, fiberglass, graphite and wood. Capable of machining parts up to 98 in. turning dia. and +/-0.001 in. straightness tolerance. Processes include milling, turning, drilling, boring, threading, tapping, forming, knurling, counterboring, countersinking, reaming and laser cutting. Secondary services such as assembly, centerless grinding, heat treating, plating and welding. Prototype and low to high volume production offered with maximum 50,000 units. Suitable for fluid power, pneumatics, hydraulics and valve applications. Serves the aerospace, aircraft, military, medical and defense industries.PTJ will strategize with you to provide the most cost-effective services to help you reach your target,Welcome to Contact us ( [email protected] ) directly for your new project.

3, 4 and 5-axis precision CNC machining services for aluminum machining, beryllium, carbon steel, magnesium, titanium machining, Inconel, platinum, superalloy, acetal, polycarbonate, fiberglass, graphite and wood. Capable of machining parts up to 98 in. turning dia. and +/-0.001 in. straightness tolerance. Processes include milling, turning, drilling, boring, threading, tapping, forming, knurling, counterboring, countersinking, reaming and laser cutting. Secondary services such as assembly, centerless grinding, heat treating, plating and welding. Prototype and low to high volume production offered with maximum 50,000 units. Suitable for fluid power, pneumatics, hydraulics and valve applications. Serves the aerospace, aircraft, military, medical and defense industries.PTJ will strategize with you to provide the most cost-effective services to help you reach your target,Welcome to Contact us ( [email protected] ) directly for your new project.

- 5 Axis Machining

- Cnc Milling

- Cnc Turning

- Machining Industries

- Machining Process

- Surface Treatment

- Metal Machining

- Plastic Machining

- Powder Metallurgy Mold

- Die Casting

- Parts Gallery

- Auto Metal Parts

- Machinery Parts

- LED Heatsink

- Building Parts

- Mobile Parts

- Medical Parts

- Electronic Parts

- Tailored Machining

- Bicycle Parts

- Aluminum Machining

- Titanium Machining

- Stainless Steel Machining

- Copper Machining

- Brass Machining

- Super Alloy Machining

- Peek Machining

- UHMW Machining

- Unilate Machining

- PA6 Machining

- PPS Machining

- Teflon Machining

- Inconel Machining

- Tool Steel Machining

- More Material